EXTRACT FOR

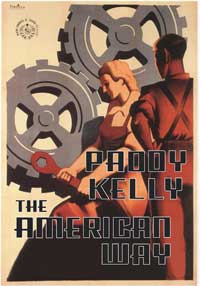

The American Way

(Author Unknown)

Prologue

At the turn of the last century, the sprawling forests which used to cover eastern Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and southern Georgia were sold by the Federal Government to private lumber interests for as little as 12 ½ cents an acre in tracts as large as 87,000 acres. This land was public domain and as such had been ear-marked for the building of houses and schools for the poor at a time when whole districts of schools were closing due to lack of funding.

Following the illegal sale of these lands, the lumber companies moved into the towns across the vast southern region, bought the judges, ousted the sheriffs and replaced them with hired gunmen who deputized their own men. Anyone who objected, including former authorities, had only to name their price or be jailed. As the prosperity of the mills grew out of all proportion to the short time it took them to establish themselves, large numbers of bodies were required to man the machines and do the dangerous work.

This problem was solved by jailing any unemployed men or small groups of men passing through the regions. Later a company agent would conveniently show up and offer to pay their 'fines' provided they worked them off. These work periods routinely lasted two to three times the illegal sentences which had been metered out. Voluntary workers seeking refuge from economic depression often found themselves in similar situations.

Pay was usually by 'time check', a check stamped, "To be cashed at a later date." If cashed prior to that date a 'cashing charge' of up to 50% was added. Paper chits or cardboard discs often served to substitute wages as well and were usually marked "Good for Merchandise Only." Merchandise restricted to what was in The Company stores and which was between 5 and 50% more expensive than the national average. If the worker insisted on being paid cash he was charged a surcharge of up to 30%, on the transaction. It was not unusual for any worker who objected too loudly to quietly vanish.

In early 1911 the only attempt to break up what in essence was legalized slavery, acknowledged on the Federal statute books as 'peonage', of tens of thousands of lumber workers resulted in the mass beatings, torture and execution of hundreds of union organizers. This with the full knowledge and endorsement of the Governors of the states involved, as well as, in several cases, President William Howard Taft. A contemporary Federal 'investigation' stated that;

We found literally every labor law on the statue books being violated. In these communities free speech, free assembly and free press are denied and time and again the employer's agent may be placed in office to do his bidding.

The report was forwarded to the White House however, no action was taken and these conditions remained in some areas for years after The Great War ended in 1918.

These were not 'isolated incidents' found only in the 'backwards' South. These working conditions were representative of the standard of the unskilled laborer throughout the United States at the time. A time when America established herself as a world leader. A political and military world leader based solely on her industrial might. Industrial might founded on the exploitation of immigrant and domestic labor.

The sole group of individuals who attempted the rescue of these workers were a small group of men and women who, in contrast to the government of the time, were dedicated to the principle that all men are created equal. A group who left a legacy, which to this day, remains written out of the American history books. They were the soon to be outlawed, (by presidential edict), labor union the Industrial Workers of the World, derogatorily known as the 'Wobblies'.

At the same time as the "Great Lumber Wars" of the South were being waged, during the worst winter on record, against one of the richest men in the world, the understaffed, financially struggling I.W.W. were unexpectedly dragged onto another Battle front . . .

'I have regarded you, not as a novelist, but as an historian. For it is my considered opinion, unshaken at 85, that records of fact are not history. They are only annals, which cannot become historical until the artist-poet-philosopher rescues them from the unintelligible chaos of their actual occurrence and arranges them into works of art.'

- George Bernard Shaw

to Upton Sinclair 5 days after

the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

INTRODUCTION

In the Spring of 1911 you could forgive New York City for its unique style of urban aesthetic. That distinct brand of romantic ambience which influenced the great Robert Henri and his collection of newspaper illustrators-turned artists. Henri's Muses?

The swelling skyline, steaming rooftops and hundreds of miles of cracked pavement and uneven cobbles. The endless rows of brownstone walk-ups and tens of thousands of clothes lines of clean laundry flapping like giant doves in the afternoon breeze above the dirty, dank horse shit-strewn streets of the isle of Manhattan. Henri's talented group were the New York Realists, later sarcastically dubbed by a cynical Press, "The Ashcan School".

However, New York, like New Yorkers, has a way of absorbing her critics. Tainting them with guilt by association and, much like China and the Chinese have managed to do across the ages, eventually assimilating them into her culture and making them her own. Of course the impressionistic forms perceived through the warm earth tones and subdued colors of the cityscapes The Realists created did nothing to relieve the bitter winters. Winters rivaling anything in Northern Europe which would gradually give way to a heat mounting daily in oppressiveness until mid-Summer when, combined with an asphyxiating humidity, became so murderous as to cause horses to faint, hundreds to die and encourage every insect within the city limits to attempt to outbreed its equatorial cousins.

Contributing to this modern, turn-of-the-century, medieval atmosphere were the babble of scores of foreign languages emanating from the 18,000 immigrants hemorrhaging into 'The City' each month. Immigrants arriving with hopes, dreams and aspirations.

Aspirations which would quickly turn to exasperation, frustration and finally desperation at the overcrowding which already stood between 600 to 800 persons per acre. A fact which the politicians and factory bosses conveniently spun as evidence of the 'Land Of Opportunity'.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but there were more Italians living in the confines of New York then there were in the entire nation of Italy.

Somewhere around 1910 the U.S. population hit 92 million, up from 76 million in 1900. In less than two years America's countable population would be 100 million. One hundred million men, women and children who required food, shelter, clothing and work.

In other words, goods and services.

The contradiction was that in a country founded on immigrant labor more than half its citizens had little or no access to the end products of the results of their labor. Worse yet, sixty to sixty-five percent of America's working population had no access to government.

Add to this social stew the fact that New York City was not only the financial capital of the nation, but there were more factories in the confines of N.Y.C. alone then in the largest most productive woolen center in the world at the time, the state of Massachusetts, and the dramatic events which were about to unfold were understandably justified.

From an industrial perspective, production quotas saw no ceiling in sight and realistically 18,000 warm bodies a month might not be enough fodder for the ever propagating factories.

With the nation's population threatening to spill over the 100 million mark, a 58 hour work week was the standard, providing the company adhered to the law, as 100 hour work weeks were not uncommon. Essentially there were no child labor laws, mandatory hourly wage laws had been stalled in Congress for the last 20 years and there was no overtime pay. Things were, as far as the manufacturing sector were concerned, looking pretty bright.

On the streets of the Lower East Side however, the only future which could be envisioned was one of diminishing hope as the exploitation of immigrant labor, increasingly sanctioned by law, broke new boundaries and climbed to ever greater heights.

The fact that in late 1911 early 1912 one hundred people a day died in U.S. workplaces, the price of a 12 cent loaf of bread varied by as much as a dollar, and there was virtually no government support for the creation of any kind of relief, counseling or immigrant education in the American system, didn't seem to slow anything down. For each one hundred that died every day, including The Lord's Day, five to six hundred got off the boat in New York City alone.

The cornerstone to free enterprise was free labor. Or at least as near to free as you could get it.

So by 1911 those coming into the country were, in a painfully unfolding reality, finding the American Dream a foreign nightmare. This of course meant that the immigrants, would have to learn the hard way. The American way.

An Englishman visiting the Little Big Horn memorial in Montana remarked that Custer's last stand was a 'tragic event'. The father of the Native American family standing next to him offered an alternative viewpoint.

"Depends whether you ate hamburger or buffalo." The heat at the bottom of the Great Melting Pot has always been a helluv'a a lot hotter at the bottom then it is at the top.

So in the Uptown districts of New York, where the heat never reached above room temperature, the ever growing plethora of 'private' clubs for the wealthy, as social diseases do, was rapidly spreading. Throughout these districts of the yet-to-be-christened 'Big Apple' pot-bellied entrepreneurs loitered in exclusive clubs, thumbs neatly tucked under tight fitting braces, sucking on over-sized, over-priced cigars congratulating each other on their business acumen and guile and how they got Manhattan Island from the Indians for a miserly $24 worth of blankets and wampum.

That is until the inevitable happened. They 'civilized' and educated the red man, made him speak their language and were able to get his side of the story.

Turns out he kept records too and not only did the Native Americans who took the chest full of pretty beads and warm blankets, no doubt with a measure of puzzled gratitude, not own Manhattan, as ownership of land wasn't a concept to such an advanced peoples, they didn't even live there. They were only down from the north for a hunting trip. None of which altered the fact that the most civilized of those Indians could never become a member of one of those exclusive 'Members Only' clubs.

The most exclusive and most politically powerful of those private clubs in the United States at the time was Tammany Hall.

The Hall was an interesting institution.

Nearly as old as the United States itself, Tammany didn't control New York politics. It was New York politics. Which was handy for the Democratic Party as the Mayoral seat of N.Y.C. was the quickest way to the Governor's mansion in Albany which, was one of the most direct stepping stones back south to #1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington D.C.

Tammany's unofficial credo was, 'anything for a vote.' and it wasn't just a motto. History duly records they did anything to procure votes.

However, Tammany was also interesting because to this day there is no universal consensus on its actual contribution to the people. Was it all bad or was there some good? There can be no question it was corrupt, but can there be such a thing as good corruption? In the mythology of the moral high ground of American idealism, no such animal exists.

To the hundreds of thousands of underprivileged New Yorkers at the turn-of-the-century whose votes were wooed, cajoled and bought by the Bosses with free picnics, a turkey at Christmas or a few quid when the rent was overdue and dad was out of work, corruption was a matter of perception. All the Hall asked in return was a vote. A pencil tick on a piece of paper. For a century and a half The Hall controlled, drove and was New York City politics and nothing short of a disaster could change that.

It was on a Saturday afternoon, out on the dirty streets of the Pig Market, Washington Square Park and Greene Street not much was different, save for the fact that the deadliest work place disaster in three and half centuries of New York City history was only about fifteen minutes away.

In the next forty-five minutes the face of New York politics would be transformed forever. By the next morning, how the nation was perceived abroad would be severely affected and by Monday morning the entire labor history of the United States would be influenced for the next seventy to eighty years and with it, how presidents would conduct their domestic business.

So it was that hundreds of thousands of Europeans, from hundreds of nationalities banded together to break tradition, cross cultural, ethnic and religious boundaries and meld into one to free themselves from the slavery of the turn-of-the-century, 'free' enterprise system.

This unification did not come quite as gradual as industrialists and their cronies in Washington would have liked or as smoothly as some twentieth century filmmakers and historians would have us believe. It occurred in only a few short years, ignited and then spurred on by spontaneously erupting, key events, the political heat of which would weld the determination of a dedicated few into the commitment of hundreds of thousands and then millions.

So, even though it might have been an Olympian challenge to cross Hester Street without getting hit by a horse cart, robbed by a pick pocket or stepping in one of those piles of horse manure, Lower Manhattan had to be forgiven, as The City had only just begun to assume the mantle of a modern day Rome. A crown she wears, to this day a century later, involuntarily, but with unapologetic pride.

Because that's the way it was in March of 1911 in New York City.

'16 tons and what'a ya get? Another day

older and you're deeper in debt.

Saint Peter, don't ya call me

'cause I can't go. I owe my soul

to the company store.'

- Chorus from the ballad 16 Tons

CHAPTER ONE

Massachusetts Federal Penitentiary

October 31st, 1920

"Sorry, visiting hours ain't till three. Yaw gonna havet'a wait." The young blond anxiously glanced at the clock. Half past twelve.

"Officer I have a one o'clock deadline! All I need is a few words with one of your prisoners. Five minutes, no more. We can talk through the bars!" She smiled and let her ankle length coat accidently fall open. The elderly guard gave a sympathetic grin.

"Who'a ya here ta see, Sweetheart?" The young woman deciphered through the thick New England accent.

"Bill Haywood."

"The Commie agitator! Nuthin' I ken do fer ya!" The guard turned and shuffled away. "Yaw gonna havet'a wait." The old man vanished as the steel door slammed shut. Resigned to her fate the reporter took a seat on the cold steel bench, lit a cigarette and waited.

Thirty minutes later a younger, shotgun wielding guard showed up and escorted the shivering woman to Block D where a matron was standing by. She was searched, her hand bag taken away, had to sign in and was taken to one of the dozens of abandoned, six foot by ten foot stone cells.

"Haywood! Visitor!" The guard announced as he let the reporter into the cell, locked the iron door behind her and remained to stand sentry outside.

The large man lying on his back, hands behind his head on the metal rack with the flat mattress and pillow didn't even afford the visitor a glance but continued to stare at the dark green, enameled brick wall.

"It's freezing in here! Don't they even give you a blanket?!"

"Red Cross day's first of the month, Sister. Beat it!" The prisoner snapped back.

"Sir, my name is Katherine, Katherine Kennedy, political correspondent for the New York Times."

Bill gave an expression of disgust and rolled over on his side.

"Visiting hours are over. Hit the bricks Kid!" Having already escaped the death penalty twice in the last twenty years Haywood was in no mood to humor a young hack with delusions that there might be a third.

"Mr. Haywood my editor has given me permission to . . ."

"To interview Big Bill Haywood before he goes to the gallows so's you can increase circulation and reel in the big bucks! That it? If you're lucky maybe you'll even get a Pulitzer nomination."

"Yeah! Hell'll freeze over before we see a woman get the Pulitzer!" The reporter quipped as she removed an envelope from her overcoat pocket and offered it to the prisoner.

"Mr. Haywood, about an hour ago our New York office received this wire from our Moscow correspondent via Berlin and London." Haywood couldn't be bothered.

"Guard! Show this lady out. Beat it kid. I need my beauty rest." The guard began to unlock the cell door.

"Sir, it has to do with Jack Reed." Haywood didn't move. "At least read the god-damned thing, you obstinate son-of-a-bitch!" Bill smirked to himself but remained motionless. In anger born of frustration the reporter opened the Western Union envelope and read aloud.

"JACK REED DEAD, STOP. APPX 07:18 LOCAL, STOP."

Bill's eyes opened wider and he stared more intently at the stones now inches from his face.

"FULL STATE FUNERAL ORDERED BY LENIN, STOP. REED TO BE FIRST YANK ENTOMBED IN KREMLIN! STOP"

Time suddenly distorted as Haywood realized the one overriding factor of the current American struggle. The struggle unfolding in virtually every other country on earth, yet ludicrously denied by the American leadership. The class struggle.

The one overriding factor? Death.

He pictured Jack's face the day of the support rally in Madison Square Garden for the woolen strikers up in Massachusetts. The same day he told Bill he was in love with Louise Bryant.

"His death will be banner headlines by the morning. By noon the New York book dealers will be back-ordering thousands of copies of Ten Days. Mr. Haywood, my editor just wanted you to . . ."

The reporter may as well have been speaking Greek. Bill was off in a trance.