EXTRACT FOR

AKWESASNE

(Author Unknown)

BOOK DEDICATION

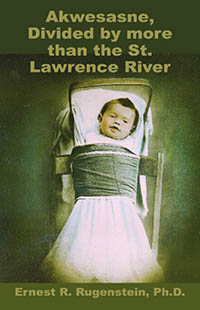

This book is dedicated to Esther M. Bonaparte. The picture on the front cover is her christening day photograph. She was born October 24, 1914, to Agnes Cree and Frank Cook of Akwesasne. The picture is exemplary of the dichotomy she grew up with. She is dressed in her Roman Catholic christening gown and swaddled on a Native cradleboard. It shows her growing up in "Mohawk" culture and living in an English world. At one point in her life, she married a white man but never was seen equal to whites.

She was a member of the St. Lucy's Catholic Church in Syracuse, NY and a member of the Kateri Tekawitha Circle. Additionally, she was a founding member of the North American Indian Club of Syracuse

On October 9, 2005, Esther Margaret Bonaparte passed away at the age of 90 years old. Her children include Joyce (the late Richard) Kelso of Ogdensburg, Honora Anne Bonaparte, Gary (Jessica) Bonaparte of Syracuse, Sheree Peachy (Richard Skidders) Bonaparte, Tami Bonaparte of Akwesasne and daughter in-law, Helen Falcone. Loving grandmother of Keli, Rick, Arron, Jason, Erich, Cheavee, Tasha, Tara, Ahtkwiroton, Stephanie, Ietsistohkwaroroks, Matthew, Ciele, Konwahontsiawi, Karonhiotha, Adam, Zoo, DonJon, Iaonhawinon, Tehrenhniserakhas, Taylor, Ienonkwatsheriiostha, Colton, Cheya, Sako. Ella, Marcey, Elcey, Jasper, Maverick, Darryl, and Havoc; and 23 great-grandchildren. She is survived by many nieces, nephews, relatives, and friends. Predeceased by her husband, Hubert Bonaparte and former husband, William Brenno; two sons, Allen and John Bonaparte; one grandson, Daryl Bonaparte; one granddaughter, Katsi-bear; five sisters, Louise Bigtree, Theresa Cree, Mae Syron, Harriett Sielawa and Ann Barnes; one brother, and Tom Cook.

One last important note, Esther was an avid New York Yankee Fan!

PREFACE

As I was preparing to write my dissertation there were two areas I was interested in. One was the minority population of Germans living in Poland after World War Two, the other was the Mohawks of Akwesasne and their interaction with the federal governments that surround them. The thrust of this book is one close to my heart. It comes from a combination of being a Cultural Historian, the fact that my wife and her extended family are Mohawk with many still living at Akwesasne, and finally my affinity for those cultures being oppressed by more powerful cultures.

I have always loved history even at a young age and I think it's because I like stories. Many times, I encounter students that will tell me, "they don't like history," or that it's "boring." I tell them that history is just that, a story. As in any account of any story, there are main characters, plots and sub-plots, and in most cases the perception of good and bad. The history of the division at Akwesasne is such a story. I have a deep interest in the history of different cultures. In particular, the minority culture that is enveloped within a major culture.

In 1989-1990 my family and I were living outside Ogdensburg, NY. The conflicts occurring at Akwesasne consumed the interest of everyone in the North Country. Roads had to be blocked and detours were needed to get from Massena to Malone, NY. My wife's extended family, being from Akwesasne gave me a unique insight into the impact of the event. The occurrences were discussed at the time with family members who often spoke about the effect it had on families on and off the reservation. Part of my family was involved also. My sister used to charter tours with Peter Pan Bus Lines from Rochester, NY to the Mohawk Bingo Palace at Akwesasne. We visited with my sister and brother-in-law at Flanders Inn in Massena, NY. This is where the excursion group would stay each night and then be shuttled each day to the reservation. My sister told me how she would advertise, charter the bus and would get the group together. The Reservation was the closest gambling opportunities at the time. People would come to Akwesasne from Rochester and Syracuse, NY and Ottawa, Ontario as well as other locations in the region. At times gun fire would erupt and busses were fired upon. Not everyone on both sides of the reservation embraced the new gambling on the one US side. Being connected to these events in so many different ways, the fact that different cultures were involved, and the historic significance of the event all piqued my historical curiosity.

The separation of the Mohawks of Akwesasne begins in a practical way beginning in the Nineteenth Century. Their reservation was "legally" divided after the War of 1812 because of the Jay Treaty. The Mohawks still suffer from being divided by two national governments and three provincial/state governments. Tribal governmental systems are imposed on either side of the border by the paternalistic United States and Canadian governments. This imposition has divided the Mohawks of Akwesasne by more than just the St. Lawrence River but by borders imposed upon them.

This book is a reflection of what occurred in 1989 -1990 at Akwesasne and the history that propelled those events. It starts with Mrs. Annie Garrow walking down the road about two miles from her house on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River to Hogansburg, NY. A trip she had made many times. She was carrying some baskets to sell. Her walk never took her off the reservation, she didn't have to cross the river. But she crossed a border that was imposed upon the Mohawks. It would lead to a US Supreme court and start a situation that eventually leads to the 1989-1990 uprising the Mohawks found themselves in.

Some have said that this was just a Mohawk Civil War, others have said that it was a squabble amongst the Mohawks over who was making money and who was controlling it. The book proposes that a system that was imposed on the Mohawks failed. If the Natives had their traditional government or at the very least a unified government that governed the entire territory, I predict this would never have escalated to the point of destruction and death. However, with the territory divided, two different governments and five administrative districts enforcing laws, the outcome was violence.

In general, no race, creed. or color has been more oppressed or had genocide committed against them as the Native American of the Americas. From the 15th century to the 18th century 95% of the Native population was exterminated. Scholarly estimates of Native American population loss are as high as 100 million. Where did they go? They didn't move, they were killed by disease (at times intentionally spread), enslaved and worked to death by the European invaders, or just killed as one would kill a bothersome coy-dog. The Natives that were left were coerced into leaving their land. This was typically accomplished through promises in treaties, none of which were eventually kept. In the case of Akwesasne, treaties imposed a border that wasn't there.

Are there different interpretations of the cause of the uprising in 1989 -1990, of course? However, as Robert A. Rosentstone tells us in his book, History of Film, Film on History, "No matter how much research we do, no matter how many archives we visit, no matter how objective we try to be, the past will never come to us in a single version of the truth." That is certainly true of this uprising at Akwesasne. The research that went into deciphering the history of the 1989-1990 uprising and placing it in a chronological order can be found in the appendix.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work's genesis is my doctoral dissertation Clash of Cultures: Uprising at Akwesasne. There are a number of individuals I want to thank for their critique of my dissertation and therefore the creation of this book. My wife and partner Keli (Keli Rugenstein, Ph.D.) is the first I would like to thank. She has read and reread this manuscript numerous times and put up with my late nights as I wrote both the dissertation and the reworking of it into this document. Without her support, I doubt I would have been able to finish.

I would further like to thank those who were instrumental in the creation of this work, offering input and suggestions. They include Professor Dan S. White, Ph.D. of the University at Albany, SUNY, Patricia West-McKay Ph.D. who is Co-Director of the Center for Applied Historical Research at the University at Albany, SUNY and who is also Director of the Martin van Buren National Historic Site of the National Park Service. Dr. Arlene Sacks, Ed.D., Chair of my Doctoral Committee and Director of the Graduate Programs at the Florida campus Of Union Institute and University (The Union Institute), was similarly a contributor to the book.

Others who have read over the manuscript and have offered feedback include Charles (Chaz) Kader and Doug George-Kanentiio both from Akwesasne. A thank you goes out to Stephen R. Walker Designs for his help with my book cover. Finally, I want to thank my sons Don and Ernest Kristoph who gave up time with their Dad so that he could do research and write.

INTRODUCTION:

What Uprising, Where? Akwesasne?

During 1989 and 1990 there was an uprising at Akwesasne (the St. Regis Indian Reservation) near Massena, New York and Cornwall, Ontario. The event was marked by violence and death, with large amounts of property and infrastructure destroyed or damaged, and families and friends torn apart. Others who were involved went to prison, were fined, or went into self-imposed exile to escape the pressures of the aftermath.

(Figure 1. Map of Akwesasne and the Surrounding Area. Page 113)

The reservation sits on both sides of the St. Lawrence River. Approximately two-thirds of the reservation lies on the US side of the border and one-third on the Canadian side.1 Akwesasne is located in part of two counties of New York State and two Canadian provinces and interacts with five different jurisdictional governments. The indigenous Mohawk culture is surrounded by and interacts with five larger cultures: the French Canadian, the English Canadian, northern New York (along the St. Lawrence River) and the cultures of both federal governments. Akwesasne has two independent, elected tribal councils that govern the Canadian and American sides respectively.

There are two generally accepted theories why the uprising occurred. One theory is that the problems of 1989 and 1990 were a continuation of an ongoing feud between the Mohawks and the US and Canadian federal governments. This feud centered upon the issue of Mohawk sovereignty, the right of free and easy access across the border, control of their land, and the ability not to be charged duties or taxes for crossing the border.2 Other sharp controversies arose from time to time, but these were the issues that caused the most friction. However, there are a few differences between the uprising at Akwesasne and the other government interactions of the past. In this uprising, traditional friends and cohorts were split down non-traditional party lines. Not only were there splits among historic allies; previously opposing sides on all other issues formed an alliance on this one. The major differences in the 1989 through 1990 uprising were the loss of lives at Akwesasne, and later at Kanesatake, (near Oka), Canada and the lawlessness and violence that occurred.

The other accepted theory for the violence at Akwesasne is it was a civil war over the issue of gambling, much like the US Civil War involved the issue of slavery. The situation was exacerbated by the response of the state, provincial, and federal governments involved, and their initial reluctance to get ensnared in the situation.

There is a yet an unexplored theory for the conflict and violence. The historical record indicates increasing conflict between the various cultures at Akwesasne since the 1950s. This intensified in 1989 and reached a peak in mid-1990. During 1989, the Canadian government, the provinces of Ontario and Québec, the US federal government, and New York State ignored requests from the elected Canadian and American tribal governments for assistance. Despite this, the elected tribal governments were still encumbered by the rules and regulations of their respective federal governments and jurisdictional considerations. The external cultural and jurisdictional restraints prevented the tribal governments to combine to settle the problems that developed at Akwesasne during this time.

By 1990, the various governments realized the seriousness of the situation but the one authority that had the greatest ability to act, New York State, did not do so until after the loss of life. The weight of this prolonged cultural conflict on Mohawk society was evidenced by the destruction of infrastructure and the blockading of roads and death. When examining the events at Akwesasne psychologically, the situational stress of the situation caused people to act out and became violent. As the stress and anxiety increased people acted violently. This scenario created stress resulted in the Mohawks acting out in a predictable manner, striking out at others. As the various systems involved broke down, stress and anxiety increased through all of the systems.

CHAPTER 1

Understanding the Politics and Institutions at Akwesasne

To understand the situation at Akwesasne, it is important to review and understand the various jurisdictions and institutions that are encountered on the reservation. These institutions include various governmental, police and investigative agencies with their associated federal, provincial or state and tribal jurisdictions. Examining the Government at Akwesasne, includes an assessment of the Longhouse/ Traditionalist government, the Canadian Mohawk government, the American Mohawk government, and the Warriors. Additionally, there is a need to investigate the relationship between the United States federal government and Akwesasne and between the Canadian federal government and Akwesasne.

Akwesasne is surrounded and divided by two federal jurisdictions: The United States and Canada. Additionally, the reservation must contend with the governments of New York State and the provinces of Ontario and Québec.3 Residents of the reservation have three area codes: 613 that covers Southeast Ontario, 514 covering Southwest Québec, and 518 covering Northeast New York. Each serves a different portion of the reservation. This division is echoed by zip codes; the American side's zip code is 13655 and the Canadian side is H0M 1A0. The population of this multi-jurisdictional community is about 13,000 people.4 Because of this unique situation, school students are also affected. Some children from the US side of the border go to Canadian schools, and all or some Canadian children go to US Head Start programs.5

There are three competing self-governments on the reservation loyal followings; the Canadian Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, the St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Council, and the Longhouse Mohawk Nation. Traditionalists from both sides of the reservation follow the rituals and traditions of the Longhouse government however the federal, state, and provincial governments do not officially recognize the Longhouse government. The St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Council oversees "funding programs from Washington and Albany" and interacts with the US side of the reservation.6 The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne connects with Ottawa for Canadian programs and agendas. Each recognized council has its band (membership) lists for its community. Technically, residents of the reservation cannot vote for both councils, however, there is nothing to stop a resident from one side of the reservation from moving from one voting roll to the other.7